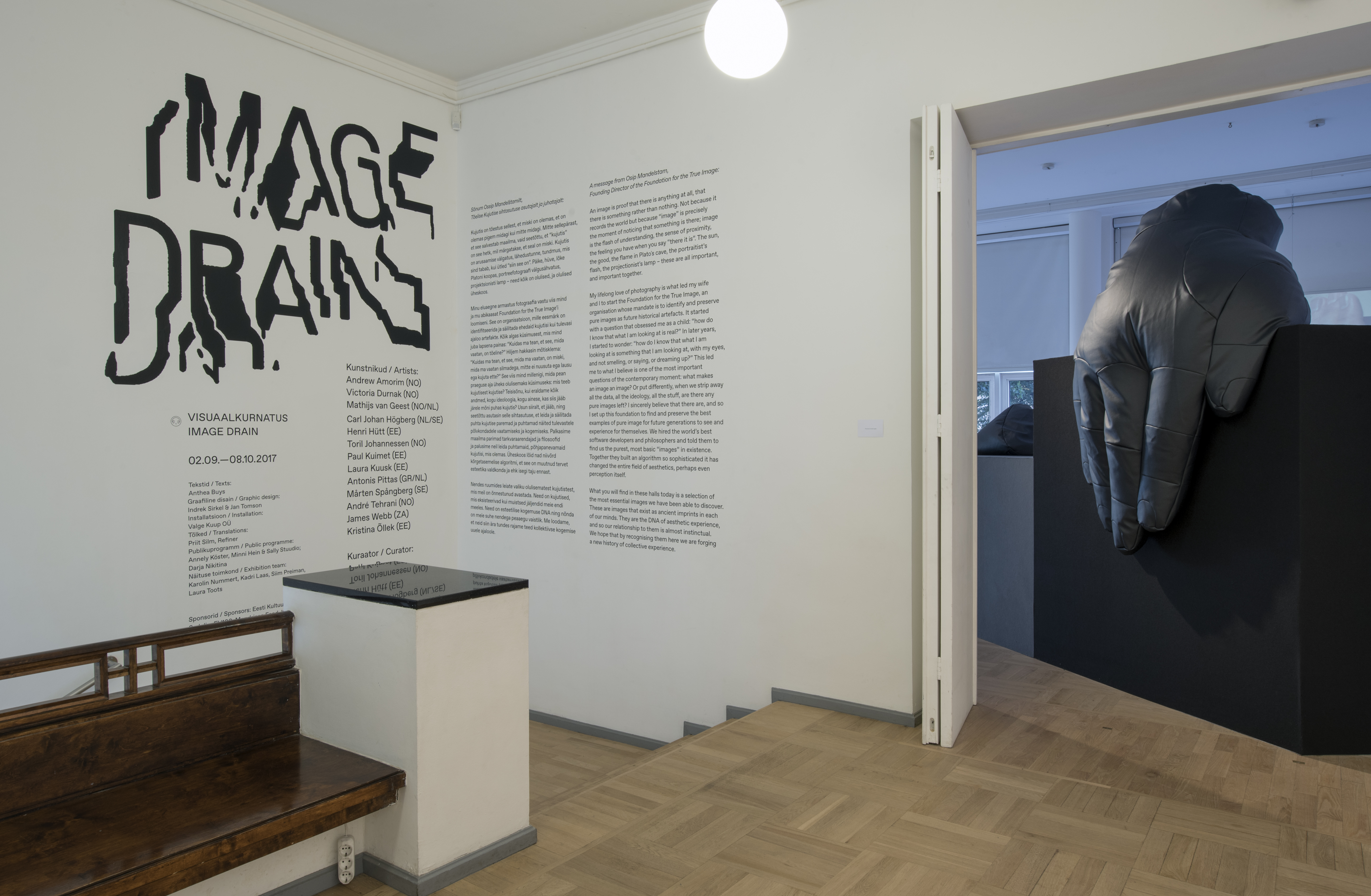

Commissioned for the Tallinn Photobiennale in 2017, Image Drain was a real exhibition that emerged out of a fiction.

Exhibition views: Karel Koplimets

Download the exhibition handout here.

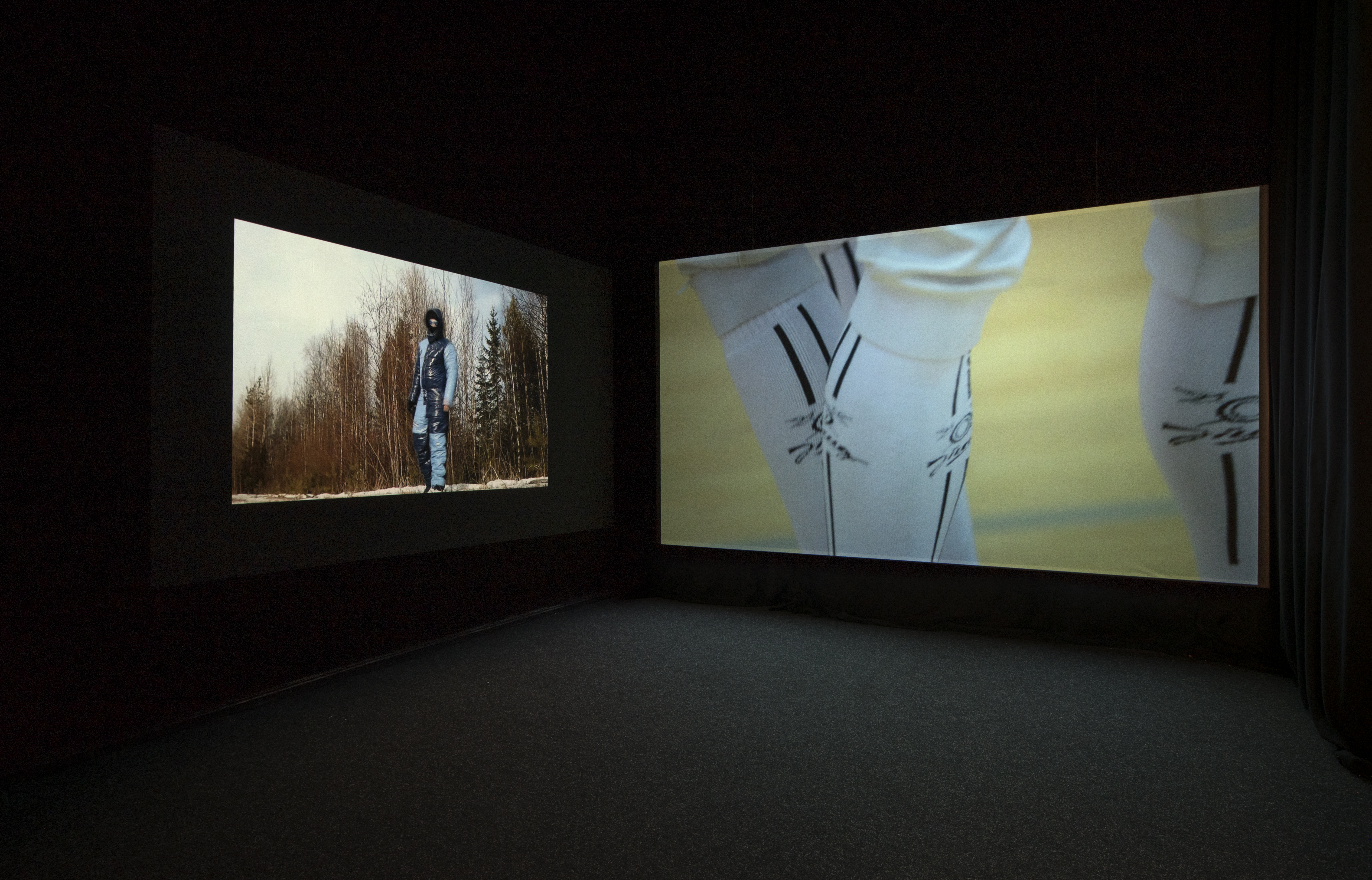

Exhibition views: Karel Koplimets

Download the exhibition handout here.

Osip Mandelstam is a venture capitalist who has fallen on hard times following the economic collapse of his home country. The automobile industry, the cornerstone of the economy, stagnated as a result of Europe-wide emergency restrictions on personal carbon emissions. The restrictions brought other industries to their knees too: travel, food, construction, sport, agriculture, and even technology. Osip owes some people a lot of money, the sort of money that justifies surreptitiously moving his family to a somnolent Baltic island under the pretence that they are on a holiday cruise. Nadezhda, the wife, hates cruises but the children tipped the scales for him. When the Mandelstams’ cruise ship docks in a quaint island port, Osip is struck by a faded yellow "Kodak" banner on the awning of a laundromat, the only business in sight other than the tourist shop. It’s been decades since he has seen that word outside of the context of American hiphop, which he tries to keep up with. Another sign with the slogan "We Photoshop while u wash!" shows that the place has moved on, a little. He definitely remembers Photoshop from his dating days, although transimage technology has long since done away with the need for any direct image manipulation.

A technical digression: much like photographs in the days of personal cameras and "smartphones", transimages are made using data skimmed from the physical world and stored en masse in "the cloud", or, as Mandelstam prefers to call it, the fizzling server that lives in the subterranean bunker he sold to HerpetoCorp Tech in 2015. One smartass intern used to joke that they should rather have called it “the oubliette”. Whatever. What most people don't know is that unlike photographs - which had to be "taken" of "something", such as a person or a cat, for example, - transimages constitute themselves in response to the desires and frustrations of whomever calls them up. The "cloud" makes this possible, of course, through the inconceivable quantity of data it archives for every one of its users, which is, basically, everyone. For the user, transimages simply deliver consistent pictorial satisfaction. There is no such thing as a bad transimage, and people are not too interested in the technical mechanisms that ensure this standard.

Osip knows all this because he invested in HerpetoCorp Tech back in the image-on-demand boom of the twenty-teens. But he sold his shares too soon.

Ugh, stupid. He has a pang of regret, and then a flash of inspiration: he will settle here, and cut a deal with the laundry boss, and turn this humble establishment into a museum of photography. He sets up a foundation, gets some trustees and finds an intern to write funding applications. Museums are good business in these precarious times - well, good business for someone whose present interest is primarily to remain out of the headlines and free of seizable assets. And in a nowhere place like this, there will definitely be a parcel of Arts Council funding for cultural development.

Another technical digression: The great thing about transimages is that they feel a lot like photographs, so much so that your average glazed-over tourist eyeball will not be able to tell the difference between a genuine photograph and an image-experience they are themselves soliciting. The great photography museums of the world ride on this ambiguity to the extent that many of the most famous photographs ever made are satisfying in the same hard-to-quantify way that transimages are. You come upon them and it’s like they knew you were coming, they regard you, they attack you, they love you. It sounds circular, and it is. Transimages are like photographs, and now photographs are like transimages. Just like the hallmark of the best homemade bread is that it looks as if it could have been bought. First bread was made for one’s own table. Shop emulates home, which eventually emulates shop.

You may wonder where Osip’s family fits into this story. Nadezhda and the two children, young, were on a ship with their holiday luggage and small toys. Their laundry begins to accumulate as Nadezhda grows frustrated with Osip's secretive lingering in the port town. He goes for long walks around the time the cruise ships come into port, the ones for which their onward tickets would be valid, and never makes it back in time to board. She suspects the front desk at the guesthouse is signing for deliveries on their behalf. And then, almost imperceptibly, she adjusts to the idea that they are not boarding any other cruise ship, not going back home, or that this is home, the guesthouse, and that she will have to do some laundry.

Months pass and there’s good news: money pours in from the Arts Council and the photography museum is a success with the cruise ship tourists. There is not much else to do at this particular dock. They enter the museum expecting to see images from the past, and so they do. The content is always old enough, but always new enough too. The transimage infrastructure work well out here where nothing competes for bandwidth, and the constant, fairly self-regulating turnover of images means that the Mandelstams don’t even have to worry too much about refreshing their displays. Nadezhda helps Osip at the museum, mostly with welcoming guests and with mediation. She tells them about some of her favourite pictures, and about the history of the town, which the former laundry boss helped with. Beyond that there is really not too much to say. The pictures are self-evident and everyone is happy. Well, almost everyone, almost all the time.

One morning Osip Mandelstam wakes up half-seeing an image inside his still-closed eyes. It's a simple pattern of multicoloured spots. They waver a little as he tries to focus on them, and it’s only when he starts to drift off again that they sharpen at the edges. Flowers? The sort that might be embroidered on a handkerchief or printed on a cheap curtain. He falls asleep again and the pattern is swallowed. Every so often, and always when his eyes are closed, the flower pattern appears like it did that morning. He wonders if they are not a memory, perhap the pattern from Kiko’s curtains, which he always found pleasant to look up at billowing above the bed when the window was open. He had been feeling guilty about avoiding Kiko’s calls, but how was he supposed to tell her any of it, the searches, the apartment, the wife, the life. Sometimes, he thinks, he can be an incredible shit. But there will always be another Kiko.

He comes to live with the fact that he is haunted by maybe-Kiko’s-curtains, that this flower thing is just what his brain does on either end of sleep. Which is fine, until the same thing starts to happen with other images, more particular ones: a soft black hand draped over a triangle, an old man with no face. They become annoyances, and then disturbances. He wants to forget them. But how can you forget something you might not have remembered? Where do these images come from, and why won't they drain properly? Are they residues from the museum? Is he making them up? Why? Osip must get to the bottom of this.

A technical digression: much like photographs in the days of personal cameras and "smartphones", transimages are made using data skimmed from the physical world and stored en masse in "the cloud", or, as Mandelstam prefers to call it, the fizzling server that lives in the subterranean bunker he sold to HerpetoCorp Tech in 2015. One smartass intern used to joke that they should rather have called it “the oubliette”. Whatever. What most people don't know is that unlike photographs - which had to be "taken" of "something", such as a person or a cat, for example, - transimages constitute themselves in response to the desires and frustrations of whomever calls them up. The "cloud" makes this possible, of course, through the inconceivable quantity of data it archives for every one of its users, which is, basically, everyone. For the user, transimages simply deliver consistent pictorial satisfaction. There is no such thing as a bad transimage, and people are not too interested in the technical mechanisms that ensure this standard.

Osip knows all this because he invested in HerpetoCorp Tech back in the image-on-demand boom of the twenty-teens. But he sold his shares too soon.

Ugh, stupid. He has a pang of regret, and then a flash of inspiration: he will settle here, and cut a deal with the laundry boss, and turn this humble establishment into a museum of photography. He sets up a foundation, gets some trustees and finds an intern to write funding applications. Museums are good business in these precarious times - well, good business for someone whose present interest is primarily to remain out of the headlines and free of seizable assets. And in a nowhere place like this, there will definitely be a parcel of Arts Council funding for cultural development.

Another technical digression: The great thing about transimages is that they feel a lot like photographs, so much so that your average glazed-over tourist eyeball will not be able to tell the difference between a genuine photograph and an image-experience they are themselves soliciting. The great photography museums of the world ride on this ambiguity to the extent that many of the most famous photographs ever made are satisfying in the same hard-to-quantify way that transimages are. You come upon them and it’s like they knew you were coming, they regard you, they attack you, they love you. It sounds circular, and it is. Transimages are like photographs, and now photographs are like transimages. Just like the hallmark of the best homemade bread is that it looks as if it could have been bought. First bread was made for one’s own table. Shop emulates home, which eventually emulates shop.

You may wonder where Osip’s family fits into this story. Nadezhda and the two children, young, were on a ship with their holiday luggage and small toys. Their laundry begins to accumulate as Nadezhda grows frustrated with Osip's secretive lingering in the port town. He goes for long walks around the time the cruise ships come into port, the ones for which their onward tickets would be valid, and never makes it back in time to board. She suspects the front desk at the guesthouse is signing for deliveries on their behalf. And then, almost imperceptibly, she adjusts to the idea that they are not boarding any other cruise ship, not going back home, or that this is home, the guesthouse, and that she will have to do some laundry.

Months pass and there’s good news: money pours in from the Arts Council and the photography museum is a success with the cruise ship tourists. There is not much else to do at this particular dock. They enter the museum expecting to see images from the past, and so they do. The content is always old enough, but always new enough too. The transimage infrastructure work well out here where nothing competes for bandwidth, and the constant, fairly self-regulating turnover of images means that the Mandelstams don’t even have to worry too much about refreshing their displays. Nadezhda helps Osip at the museum, mostly with welcoming guests and with mediation. She tells them about some of her favourite pictures, and about the history of the town, which the former laundry boss helped with. Beyond that there is really not too much to say. The pictures are self-evident and everyone is happy. Well, almost everyone, almost all the time.

One morning Osip Mandelstam wakes up half-seeing an image inside his still-closed eyes. It's a simple pattern of multicoloured spots. They waver a little as he tries to focus on them, and it’s only when he starts to drift off again that they sharpen at the edges. Flowers? The sort that might be embroidered on a handkerchief or printed on a cheap curtain. He falls asleep again and the pattern is swallowed. Every so often, and always when his eyes are closed, the flower pattern appears like it did that morning. He wonders if they are not a memory, perhap the pattern from Kiko’s curtains, which he always found pleasant to look up at billowing above the bed when the window was open. He had been feeling guilty about avoiding Kiko’s calls, but how was he supposed to tell her any of it, the searches, the apartment, the wife, the life. Sometimes, he thinks, he can be an incredible shit. But there will always be another Kiko.

He comes to live with the fact that he is haunted by maybe-Kiko’s-curtains, that this flower thing is just what his brain does on either end of sleep. Which is fine, until the same thing starts to happen with other images, more particular ones: a soft black hand draped over a triangle, an old man with no face. They become annoyances, and then disturbances. He wants to forget them. But how can you forget something you might not have remembered? Where do these images come from, and why won't they drain properly? Are they residues from the museum? Is he making them up? Why? Osip must get to the bottom of this.