Artist imagines a world in which black excellence is not seen as an exception

First published here.

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi tells Anthea Buys about her powerful solo show, 'Gymnasium', and why she refuses to pander to the 'alien narrative'.

For artist Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, the art world is like a gymnastics tournament. The people who matter most – artists – bend over backwards for recognition, and the ones doing the recognising are still, overwhelmingly, white audiences and king-makers. In the world of gymnastics, the unprecedented skill of African-American athlete Simone Biles has altered how the sport itself functions. For a young, black, female athlete to ring such changes in an arena that has been dominated by white bodies and voices is, sadly, exceptional. In art, despite there being many a Biles, transformation is slower still.

When I visited Nkosi in her studio a few weeks before the premiere of her first ever solo exhibition, she was racing to complete a series of paintings of scenes from competitive gymnastics. Titled Gymnasium, her latest collection of paintings and video will be exhibited at Stevenson in Johannesburg from 26 March, and will be available for viewing through an interactive online 3-D viewing room accessible from the gallery’s website.

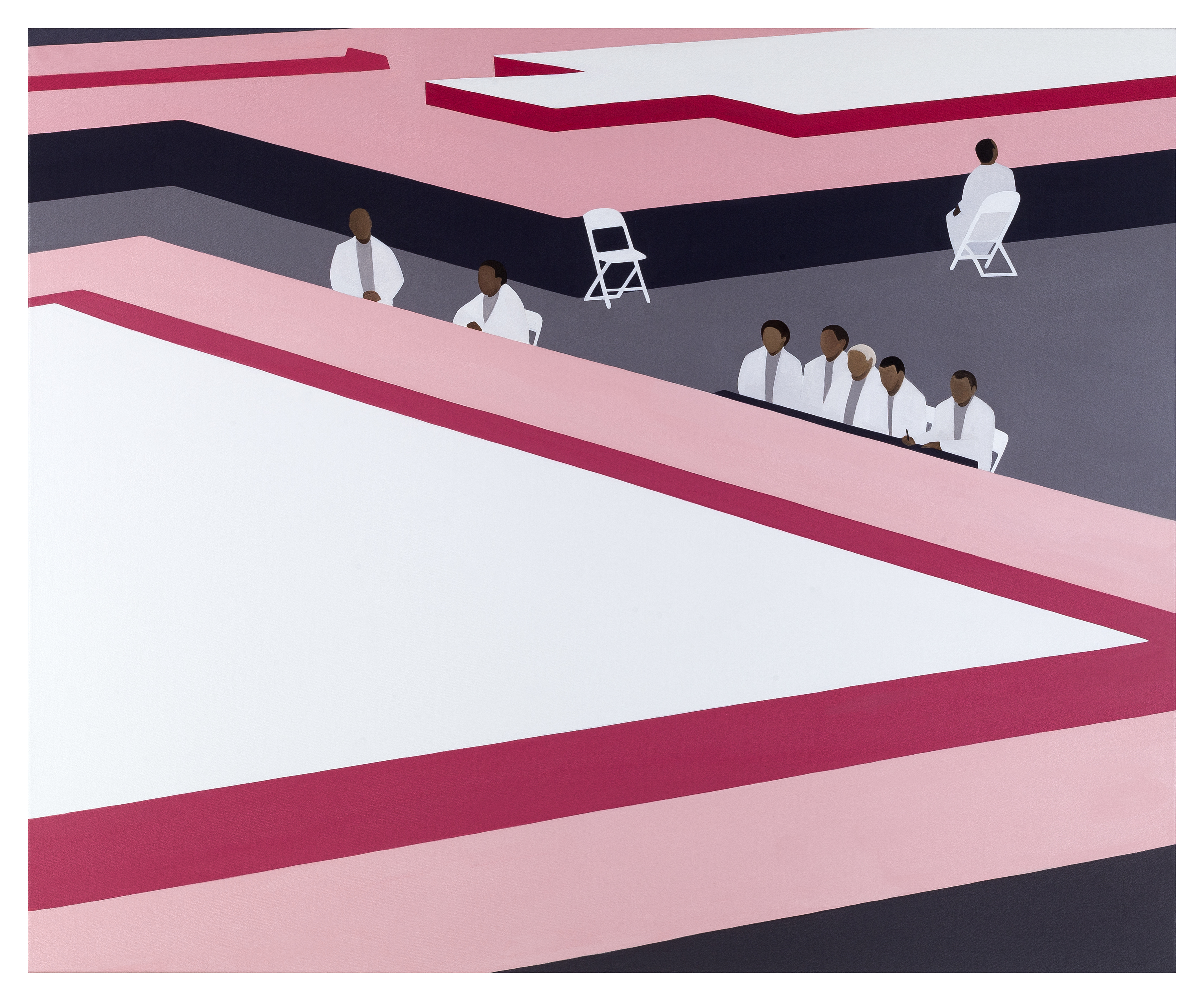

Gymnasium imagines a world in which black excellence is not seen as an exception. The subjects in her paintings, from gymnasts warming up, to cameramen, to crowds of onlookers, are all black, a move that highlights the conventional whiteness of the sport and its audiences. The seated black audience in the work Audience (2020), for instance, was adapted from a reference photograph of an all-white audience, simply because pictures of crowds of black people at leisure – never mind crowds of black people at gymnastics competitions – are hard to come by.

The enduring whiteness of gymnastics may seem arbitrary, but it is in fact deeply rooted in right wing ideology. Following the Great German Gymnastic Festival of 1933, presided over by Hitler himself, it became the most popular sport in Nazi Germany. Combining grueling physical exercises with elements of ancient German dance, artistic gymnastics was believed to be the technique by which the Nazis would produce an elite squadron of Aryan uber-bodies. Gymnastic performances were propaganda, proud demonstrations of the physical prowess of the master race.

This is why painting black gymnasts scrutinized by black judges and performing for black audiences is a poignant re-imagining of the past and the present, and a kind of anti-propaganda, a purging of the remnants of white power ideology. “What I’ve wanted my work to do for a long time is to talk about power,” Nkosi offers. “And power is about voice, who gets to talk and who doesn’t, and who gets space to be heard or remembered or just to be.”

For years Nkosi has found it hard “just to be” in an art scene that has kept her somewhat on the periphery. Born in New York to exiled South African and Greek-American parents, and educated between South Africa and the United States, she has always moved between worlds. Even her artistic practice has been a constant negotiation between genres, with her output divided between painting, video, and collaborative social intervention. Nkosi is prolific. But without the long term backing of a gallery, which gives artists a degree of visibility that is difficult to generate on their own steam, the ascent of her career has been sluggish.

Briefly represented by the Seattle-based Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, she had no footprint locally other than her studio in Johannesburg’s Victoria Yards. South African galleries flirted, inviting her onto group exhibitions, but until six months ago none had committed to representation. Now Nkosi has joined the stable of Stevenson, a leading South African gallery for contemporary art, and, perhaps inevitably, her visibility is catapulting.

Given that she was featured in a solo booth presentation at the art fair Frieze New York in 2019, and that Artnet.com named her painting Routine (2019) one of the top six works in the fair, it seems a staggering oversight that Gymnasiumis only Nkosi’s first solo exhibition. In October 2019, taking a step to ameliorate the lapse, the prestigious Africa Centre in New York premiered a new mural commission based on three paintings, all from 2019, The Judges, Tally and Fault.

How is it, in light of this international attention, that Nkosi has remained relatively obscure in her chosen home country? Just as there’s more to professional gymnastics than having the right coach, there are more complex dynamics in play than gallery representation. As a black painter influenced by formalism and working in a minimalist vein, she is an anomaly in an art market that has fallen in love with, on the one hand, the expressive abstraction of painters like Meshack Masamvu and Portia Zvavahera (also represented by Stevenson), and, on the other, the symbolically overdetermined figuration of Yinka Shonibare MBE and Kudzanai Chiurai. Nkosi’s problem seems to have been that she does not fulfill one of these two narratives – the black artist as expressionist or the black artist as symbolist – in the white imagination. “For me white audiences play such a major role in the art market,” she says. “Black artists have been making all kinds of work for a long time, but the thing that gets consistently foisted upon us is that we have to make this accessible to a white audience via your particular ‘alien story’, your black story, your other story.... It feels like it needs to have that exoticism in order for it to be consumable and interesting.”

Nkosi’s work is an antidote to the alien story. We see the figures in her paintings in various states of preparation and waiting, the banal moments outside of the main event. These are universal slices of time, ones we can all relate to at some level. Nkosi’s athlete, now stretching, now embracing a teammate, is the everywoman. Unlike her earlierHeroes series, which consists of portraits of people, both iconic and unknown, admired by the artist, the figures in her new paintings are faceless. These anonymous “portraits” are ciphers that anyone can imagine their way into. This is because black experience is relevant to everyone, to “the world”, in Nkosi’s words, not just to discourses about blackness. “When we’re talking about blackness, let’s complicate it,” she says. “Let’s talk about what blackness is revealing more broadly. Let’s talk about how thoughts coming from people of colour are complicating the world.”

View Gymnasium here.